Cuneiform, the ancient orthography used by Near-Eastern civilizations

from 3500BC to the first century in the Common Era, is significant not only

because it represents mankind’s shift from pre-history to history- people

describing ideas in their language on their terms, but also because it gives us

great insight into the languages of the ancient Near East: Sumerian, Akkadian,

Elamite, Hittite. All of the information we have about the onset of human

civilization in the Near East has been facilitated by the fact that we were able to

phonetically analyze the scripts of these dead languages and draw conclusions

based on the way we know language works. This post will discuss how

Cuneiform transformed from its use as a seal and record-keeping tool by the

Sumerians, into a full written language, and how this script was then taken and

changed by surrounding civilizations in order to fit the phonetics and syntax of

their own languages.

Some historical context is important to frame Cuneiform and its

significance in the ancient Near East. With the onset of the Neolithic revolution

between 5000 BC and 3000BC, mankind was undergoing its most significant

transformation- the discovery of agriculture and the push to form larger settled

communities. No other region in the world could have been more suited to

creating this than the Near East, which had at the onset of this revolution had the

largest urban populations in the world. Sumer, on the borders of the Euphrates

River in what is modern day Iraq, had some of the world’s first cities, with the

largest, Uruk, having a population of somewhere between 50,000 and 80,000

people(a far cry from the bands of around 30 people that had populated the preneolithic era just centuries before).

These urban populations represented mankind’s first experiment with large-scale interactions, and with these large

scale interactions came the need to keep records of some sort.

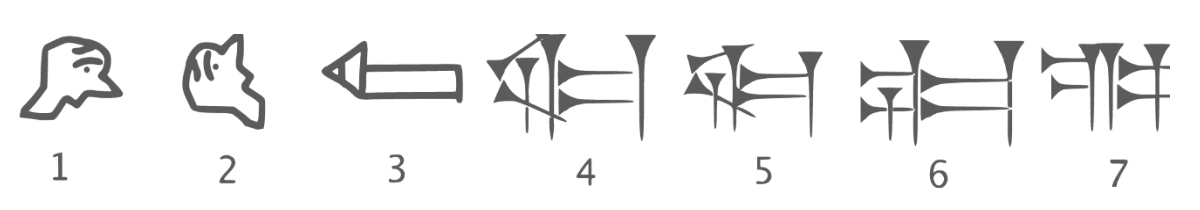

From around 3500BC to 3200BC, the Sumerians represented these records

as pictures (usually of cattle or grain or other tangible items). This process is

paralleled, slightly later, in the blooming urban centers of the Nile Delta, and in

Northwest India with the seal inscriptions of the Harappans slightly thereafter.

These pictographs eventually transformed into the idea that these pictures

represented(ideographs). The evolution of the Cuneiform script from the seal and

record symbols to the Cuneiform as we know it today was a process that

happened relatively quickly(over a period of 500 years from 3500BC to 3100BC) .

SAG: “HEAD” Logogram Evolution:

Sumerian, at the onset of this change from pictograms to ideograms,

would have been impossible to read accurately, had it not been

for the fact that some of these pictograms came to represent sounds in a

language, rather than ideas. Cuneiform built words with these two kinds of

characters- ideograms that evolved from related pictograms, and proper

phonetic symbols that came to represent the sound(or part of the sound) that the

pictogram represented. Thus, the word for “star” in Sumerian could either be

represented as: 𒀯, the ideogram, or phonetically as the symbols MU and UL, to

form the word MUL, 𒈬+𒌌, which is how the Sumerians would have

phonetically pronounced this word.

Sumerian, also used special characters that were not pronounced at all but

used to aid the scribe or the reader- determiners. Determiners, which are very

common in languages that are analytic, including Chinese, are placed next to

words in order to categorize. For example, the 𒁹 followed all male personal

names. 𒌷 is the symbol is put before (or sometimes after) the name of a city or a

large settlement, which is why the great capital of the Sumerians, Uruk, was

spelled out 𒌷𒀔, with the first symbol being unpronounced and the second

being an ideogram of the city. The Sumerians also did this for female names,

names of trees (and in fact, all things made out of wood), countries, people and

ethnicities. Though these were not pronounced in Sumerian, the other Cuneiform

scripts would fossilize these determiners as well. Sometimes, a determiner could

also be an ideogram, as in 𒀯, which discussed above as an ideogram, was also

the determinative placed right after the names of all stars.

The Sumerian Language recognized at least the following consonants: b,

d, g, g̃, ḫ, k, l, m, n, p, r, ř, s, š, t, z. They clearly made a distinction between

alveolar stops (t,d are distinct), alveolar and bilabial nasals (m and n are separate),

as well as velar nasals as in g̃. In addition to the b,d,g,k,l,m,n,p,r,t,z, which are also

part of English phonology, Sumerian has velar fricatives, ḫ or x. It also has the

affricate /ř/ that was most likely produced as a voiceless aspirated alveolar

affricate. The vowels in the language are /a/, /e/, /i/, and /u(with /o being

discussed later as a possible vowel).

Excluding the Sumerian ideograms, the orthography of this syllabary was

very consistent, and obviously worked with the Sumerian phonetic

system(because they themselves made the written language). The syllables

followed the V or CV or VC form (MU+UL). There was no difference in Cuneiform

between voiced and unvoiced stops(b and p use the same symbol, for example).

Sumerian is an agglutinative language, created by stringing morphemes

with separable prefixes or suffixes (several of these could be chained onto the

root morpheme to make the meaning more complex). In addition, most words

were monosyllabic. With only 16 consonants and 4 vowels, there are at max 132

different combination for monosyllabic words (CV, VC, and V combined). It should,

then, come as no surprise that Sumerian has a vast number of homonyms, so

many in fact that most linguists are convinced that there must have been some

phonemic difference to separate these homonyms. For example, the language

may have been tonal, or perhaps had a pitch accent, or differ in length or have

some other sort of phonemic distinction; the issue is the writing leaves no clues

to what this difference may have been. Therefore, while Cuneiform may have

been a very good system for the monomorphemic and analytic language, it may

still be insufficient in describing all of the phonemic differences that may have

existed in the language, and in any case the speakers of Akkadian and Hittite

speak languages from families which notably lack any tone, so this would not

have been carried on after the death of Sumerian.

Continuing with the question ambiguity above, there also exist many

questions about the way Sumerian was pronounced that are up for debate. For

example, would MU+UL do what many languages naturally do and just assimilate

into MUL? Would MU+UL be pronounced slightly longer, or with a glottal stop,

as it might be pronounced in the Semitic Akkadian? As a language isolate, there’s

really no way to compare any documented language to Sumerian and construct

some sort of proto-language that could be used in aiding the phonologist. In

fact, for that matter, how do we know what any of the syllable-consonant clusters

sound like at all? How were these forms conjectured? If it seems as if making any

conclusions about Sumerian is superfluous and based on too much conjecture,

that’s because it is; most of what we know about Sumerian in and of itself is not

enough to draw any conclusions about the way it was spoken or written.

The way we know anything about Sumerian at all- what the syllables map

to phonetically, the sounds likely common in the language, the “illegal”

sequences of the language- is because of another language that came to

dominate the region.

The Akkadians, originally from parts of the Western Levant,

settled north of Sumer on the banks of the Tigris and conquered the city states

around it, eventually even defeating Sumer around 2300BC and absorbing it into

its growing empire. Rather than ending the Sumerian language and orthography

completely, however, these new kings who would ironically ensure that

Cuneiform would long outlive the people who originally made it.

The Akkadians also had the task of using Sumerian Cuneiform to fit the

phonetics of their own language. This was not a simple task.

Akkadian, unlike Sumerian, is a Semitic language. It is also agglutinative, and doez

not have the velar nasal or the voiceless aspirated alveolar affricate. It did on the

other hand have the q, ṣ, ṭ, emphatic stops, have phyringial affricates, and glottal

stops, none of which were part of Sumerian. As a Semitic language, it tended to

form triconsonental roots, without any regard to the vowels. Sumerian, on the

other hand, required both a vowel and a consonant in order to write the CV and

VC clusters. Many of its words were multisyllabic, while Sumerian was mainly

monosyllabic. Analyzing these difference between the (same) Cuneiform script reveals that the

the emphatic ṣi is realized as a zi, and the emphatic ṭu as a du.

The Sumerian language had a huge influence on Akkadian; there is

evidence of massive lexical, syntactical, and phonological borrowing during this

time. The Sumero-Akkadian Sprachbund was unique in that it was not only lexical

items that were shared and borrowed, but also syntax: the VSO order of Akkadian

came about because of influence from Sumerian. Sumerian remained the

language of religion and culture, much as Greek did in the Roman world, and so

Akkadians continued writing Sumerian, mainly in religious services, hundreds of

years after the language had ceased to be functional.

The fact that Sumerian was seen as a language of religion created a

fascinating phenomenon in Akkadian: Sumerograms. Akkadian did not only

borrow ideograms from Sumerian, but also the words that were spelled out

phonetically in Sumerian (like the word for star 𒈬𒌌) and kept that way in

Akkadian as a sign of respect for the Sumerian language itself . These words

would become ideograms in the unrelated Akkadian language. So if an Akkadian

saw the word 𒈬𒌌they would read the Sumerian “MUL” but pronounce it in

their own language, “KA-KA-BU”(star). In essence, thousands of combinations of

Sumerian words became ideograms in their own right. This idea would later be

extended even further to include Akkadograms- phonetic spellings of words in

Akkadian- that become ideograms in Hittite.

In Akkadian, the choice of writing words phonetically, using borrowed

ideograms, or using Sumerograms seemed to be mainly stylistic, and the words

themselves were understood to be equivalent. Logography seems to be more

prevalent in certain contexts, like legal documentation. Akkadian played a key role in deciphering Sumerian. Akkadian, unlike Sumerian, is very closely related to the living Semitic languages.

Cuneiform’s ability to be used for different language families did not end

with its extension to Semitic language. The first evidence we have of any IndoEuropean language in writing also came to us in the form of cuneiform. The

Hittites who called themselves the Neshli, spoke an Indo-European language from a

now extinct branch of IE called the Anatolian languages. They thrived in Hattusa,

the region which is today in northern Turkish Anatolia, and learned how to use

cuneiform not through conquest like their Assyrian counterparts thousands of

years earlier, but rather through cultural diffusion around 1300BC, over a

thousand years after Sumerian had given way to Akkadian.

Hittite phonology contained key differences to both Akkadian and

Sumerian. While Akkadian had the three-consonant clusters of vowels that were

then used to build sentences, and Sumerian was mostly monomorphemic, Hittite

was a less analytic and more synthetic language, which, like many other Indo-European languages, had many case endings and markers that were not as free

as they would be in an analytic language like Sumerian. The Hittite language had

the following sounds in its phonology: b, d, g, ḫ, k, l, m, n, p, r, š, t, z. However,

like Sumerian, there is no difference between voiced and unvoiced stops, leading

to some ambiguities in the writing. However, because of what we know about PIE

and its descendants, we can be certain that, like Sumerian , Hittite in fact did

distinguish between these two.

Still, the practice of writing Cuneiform seemed to be so standardized that

even by this point in time, the orthography had changed very little, with the

exception of the Sumerograms and the Akkadograms that had come over from

Mesopotamia. Where Akkadian sometime failed to resolve ambiguity about

Sumerian, Hittite became vital, as no other language family had been so

extensively researched and documented as the Indo European languages.

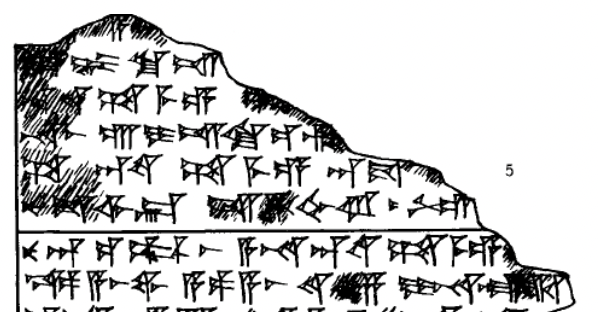

Below is the Hittite rendition of the Sumerian epic, “Gilgamesh”.

KBo 6.1 First panel of the Hittite version:

- a

- uk? ki iš

- ša me e

- na aš úI iš ki iz

- ša an [Sumerogram]

ša me e an da

- ši ka ar iš ??ah ru ga

- nu an [Sumerogram] aš a mu na [Sumerogram] ša me e

- ka a aš ua(wa?) a pa a aš ??? za la [Sumerogram]

- ku-it [Sumerogram] ri [Sumerogram] pa a še ša nu-ut

Hittite is fascinating because of the way it take Sumerian and Akkadian

words and grammar and applies it to a totally different language family. For

example, Akkadian liked to use small separable prepositions(in, under, for) and

actually had more (positional) prepositions than any of its Semitic descendants.

The word LUGAL in Sumerian meant “king”, and this word was borrowed,

phonetically and lexically, into Akkadian. So the phrase “ANA LUGAL” meant “For

the King”. Strange things happened when this phrase was eventually used in

Hittite. Hittite, as previously stated, is full of case endings: -s, -e, -n, -as, -i, -az, -

anza, -a, and -it. These case endings were very important semantically. The word

for King in Hittite is hassu and attached to the end of this word is the dative case

used to indicate for. While the phrase may have been pronounced hassu-i,, it was

spelled first with the Akkadian preposition ANA, followed by the Sumerian

ideogram LUGAL, followed by the -I in phonetic cuneiform. ANA LUGAL and

HASSU-I could hardly be more phonetically different, and represent the vast differences

between the three language familie In some ways the

respect and care these cultures took to preserve the “correct” form of spelling for

languages that died out hundreds, and in the case of Sumerian, thousands of

years prior, represents a cultural exchange of languages, ideas, and convention

over millennia in the Near East.

So Cuneiform, once only used to write a language isolate on the lower

Euphrates, eventually long outlived its last speakers, surviving from 3000BC until

2000BC. Akkadian, which had borrowed so much from Sumerian, nevertheless

used Cuneiform to varying degrees of success for the very different Semitic

Akkadian language. The orthography of Sumerian, once one-to-one(except for

the fact that it didn’t differentiate between voiced and voiceless stops) no longer

followed the phonemic principle in a Semitic language that cared little about the

vowels that the monomorphemic Sumerian found so important. Sumerian

fossilized as a religious language, but was nonetheless revered and admired long

after its death. Hittite, millennia later, borrowed language through the lens of the

Akkadians, and unlike the Akkadians, started adding symbols in order to fit their

vocabulary. The Hittites, who existed around 1600BC to 1300BC, changed

Cuneiform to fit their own grammar while still keeping lexical, and even

grammatical elements that exist as a sort of vestigial feature of the language.

That Cuneiform could exist throughout millennia speaks to the respect and

admiration, as well as the malleability, Cuneiform held in the region.

Works Cited:

E. Rieken et al. (Ed.), hethiter.net /: CTH 341.III.1 (INTR 2009-08-12)

KBo 6.1 “Gilgamesh: First panel of the Hittite version”

Pearce, Kristin M. (2010) “The Adaption of Akkadian into Cuneiform,” Colonial Academic Alliance Undergraduate Research

Journal: Vol. 1, Article 2.

Cooper, Jerrold S. 1996. “Sumerian and Akkadian.” In The World’s Writing Systems, ed. Peter T. Daniels and William Bright,

37-58.